An edited version of this text is featured on The Marshall Project

By Richard Ross

Just north of the city of San Francisco, across the bay at the tip of the Marin County, stands San Quentin, California Men’s Prison. The crenelated castle-like towers remind you it was built when Abraham Lincoln was still President. It is also the home to the only gas chamber and death row in the state with 550 condemned men.

It is also the work place of Mandi Camille Hauwert, the only transgender correctional officer on the staff.

Every work day, she walks into a hyper masculine world. In addition to the 4,000 male prisoners, many of the corrections officers are former military, forming their own band of brothers. As James Brown sang, “It’s a man’s man’s man’s man’s world.”

Hauwert had entered the correctional system after four years active in the Navy, deployed in the Pacific as a damage control and assessment officer. However, in early 2012, after seven years of working at San Quentin, Mandi ceased to hide her true feelings. She began to wear earrings and makeup and let her hair grow.

Mandi, 35, shows me her correctional academy graduation picture with her parents. It is not easy to recognize the broadly mustached officer as the blonde woman in front of me.

Six feet tall and solidly built, Mandi has been taking hormones for almost three years. She says they often make her emotional and teary. She’s especially emotionally as she recounts the number of times she is hurt by “gender misidentification” during her work day—when the guards and prisoners still refer to her as masculine instead of feminine. In fact, she has been sent home several times for crying, although it is nothing she can easily control.

An occasional misidentification of gender might be chalked up to preponderance of men in this world, but the body language of the world around her is often far from subtle. Two or three men, guards as well as inmates will stop a conversation, angle closer to each other and exchange words in a hushed tone as their eyes follow Mandi. Sometimes it is louder and more specific. The most insulting comments are from the inmates just coming into the system. Mandi says she’s heard comments like: “He’s just a fucking faggot with a fetish for women’s underwear.”

The people who do treat her with respect are usually those who get to know her better. “When the population knows me and knows who I am, they usually accept me more as a person,” Mandi says.

Still every day can be an endurance trial. “Being inside the prison everyday, it's tearing me apart,” Mandi says. “ It's erasing the sense of myself, my feelings of self worth.” She adds, “I believe it is partly the military mind-set which disallows flexibility when considering gender.”

In the prison with four cellblocks stacked five tiers high, the environment is pure masculine. Among the guards, who are primarily African-American, one of casual forms of address is “brother,” accompanied by clasped hands brought to the chest, an embrace and three solid pats on the back. But Mandi is not a brother. White, broad shouldered, she is nobody’s brother. While some people treat her with respect, others can be hurtful.

In the guards’ tan and black uniforms, gender is difficult to differentiate. Although her badge is the same, Mandi’s uniform is slightly different than those of her colleagues. She wears pants, but they are cut slightly differently than the men’s, and instead of a long black masculine tie, she wears a short, crossed ribbon. Her blouse also has pleats and buttons right over left rather than vice versa. Her long sandy blond hair is often tied up. She wears make up and has her nails done. Her voice with the inmates and peers is gentle and demure.

The ability of the institution to embrace her has been slower than she would like. She did receive formal notification about proper dress code and all the formal State of California notification as to her rights, but she was warned that “cross-dressing is not allowed.” Although the formalities hinted at what she might expect as a transgender, it is hard to translate that into a warm environment. If an individual worked, for instance, at the Berkeley campus of the University of California, which is just south of the prison, the transformation might be significantly easier--but this is California Men’s Prison.

There are three transgender inmates at the prison, Mandy notes. They are chromosomally male, and so they are housed at the men’s facility. Likewise those who are chromosomally women, even if they identify as male, are housed at the women’s prison.

Mandi’s work responsibilities are primarily patrolling the visiting room for inmates and visitors. Juan Haines, an inmate and managing editor of the San Quentin News, describes Mandi as one of the kinder officers in the system. He said, “Many of the guards feel that since you are in prison you are undeserving of kindness and love. They don’t realize that my job on visiting day is to be a father to my daughter. Mandi gets this and helps make visits positive.”

Mandi’s Facebook page reveals an open longing about what family means to her. She has been fortunate enough to be embraced by her mother and father, and Mandi herself openly laments her inability to have children. Transgender people are not allowed to adopt in California.

Her postings are a wealth of self-reflection—a complex narrative of the journey she has embraced since she came out to the prison staff. She is painfully candid and honest: “Each and every day I rediscover little parts of myself that have been long forgotten, or just never before accessed,” she wrote in one recent post. “I do not know, & I cannot say what the experience of growing up as oh girl is like, but what I can say with absolute clarity and certainty, is the experience of transitioning to womanhood later in life, is nothing short of mind blowing.

This transition is documented with an almost continual stream of selfies—mostly headshots of a shy but almost glamorous looking woman.

Mandi doesn’t write about any complaints against her work colleagues, as she fears more discrimination. “I have existed in a military or paramilitary world all my life,” she says. “I know how this works. And where would I start? I am misidentified by pronoun not once or twice a day but tens, hundreds of times a day—it’s endless and it’s crushing. It’s not worth it to me. It’s like Chinese water torture---one drop at a time, one pronoun at a time, one snide comment and aside---one after another. It’s torture.”

Still she knows that others have had it worse. Mandi herself attended the same junior high school in Oxnard where, in 2008, a 15-year-old gay student was shot twice and killed by another student. The assailant eventually pleaded guilty and received a sentence of 21 years.

Mandy’s “gender affirmation” surgery is scheduled for March. One advantage of her prison job is that the procedure is covered by her corrections officer insurance.

“I’m glad you are doing my story,” Mandi tells me. “I would hope the outcome would be to make life easier for other transgender people. Let's just say I'm not used to positive thinking and have not anything positive in my life in a long time. I have never really smiled much, but part of that also has to do this growing up depressed.”

She admits: “Yes, I am anxious” about the upcoming operation, as she sweeps a lock of her blond hair from across her face with her perfectly manicured nail tips--clear lacquer to comply with prison regulations. But she adds, “I will be home recouping with my family. My parents support me, and I am intensely close to my sister. My brother, who is a devout Christian, has disavowed me.”

It’s April now, and I’m wondering how it came down to this, and how I stooped this low, and how I am in here because of these so-called friends.

It’s April now, and I’m wondering how it came down to this, and how I stooped this low, and how I am in here because of these so-called friends. This cell is so small sometimes I think I am living in my bathroom. My bunk is welded to the wall, and I have a thin mattress and two thin, brown blankets. There is toilet paper hanging from my ceiling, lots of gang writing carved into the walls. All I can see are white bricks and my purple steel door.

This cell is so small sometimes I think I am living in my bathroom. My bunk is welded to the wall, and I have a thin mattress and two thin, brown blankets. There is toilet paper hanging from my ceiling, lots of gang writing carved into the walls. All I can see are white bricks and my purple steel door. As I walk down the stairs from my cell to the day room where there are four tables with four benches around each, I think about how every day is exactly the same and how I am so used to this.

As I walk down the stairs from my cell to the day room where there are four tables with four benches around each, I think about how every day is exactly the same and how I am so used to this.

I was born in San Bernardino, now I live in Culver City. I live with my mom and dad. They visit me as well as Po Po, my grandpa. My mom is in school, my dad is out of school and he’s about to work. I have four younger brothers, two older brothers and a younger sister. At home I have my own room. We have a four-bedroom house. In one room three of my brothers live but I have my own room and so does my older brother. The other kids have bunk beds. This isn’t my first time here . . . but it is my last. I was doing something I wasn’t supposed to be doing. I think I want to be a mechanic. I want to be able to fix almost anything.

I was born in San Bernardino, now I live in Culver City. I live with my mom and dad. They visit me as well as Po Po, my grandpa. My mom is in school, my dad is out of school and he’s about to work. I have four younger brothers, two older brothers and a younger sister. At home I have my own room. We have a four-bedroom house. In one room three of my brothers live but I have my own room and so does my older brother. The other kids have bunk beds. This isn’t my first time here . . . but it is my last. I was doing something I wasn’t supposed to be doing. I think I want to be a mechanic. I want to be able to fix almost anything.

Last week, we brought you inside Santa Maria Juvenile Hall to meet

Last week, we brought you inside Santa Maria Juvenile Hall to meet

Cheryle:

Sometimes I wish we had left the country. We had that weekend, we could have run away. But we had no idea. We knew he was innocent. We went on vacation. We were so naïve. I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen. Looking back, there were so many things I would have done differently. But you can’t go back. It was the first time we’d been involved in the juvenile justice system. We hired a lawyer we heard was very good. We paid a fortune. My daughter sold her house to pay for him. He let us down immensely.”

[superquote]I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen.[/superquote]

One of my biggest regrets, since we were all going to testify as witnesses, we couldn’t be in the court during Anthony’s proceedings. We waited in the hall every day, waiting to go in, waiting to hear news. Since we weren’t in the room, we couldn’t know exactly how bad our lawyer was.

The juror selection was completely unjust: how was it that when I looked across the room at the jury pool I recognized so many faces? Lake County is HUGE, why couldn’t they pull a more diverse selection of jurors? One of the jurors was from our little community. He was an Elk’s Club member. His wife and the prosecutor’s mother knew each other. This juror gave another juror a ride home to Whiting each day, discussing the case in the car. The trouble with this juror began when he was first selected. He was a neighbor of a niece; it was not a friendly relationship. We knew that it would be wrong for him to be on the jury. My daughter wrote a note during jury selection and asked our lawyer not to allow this juror on the jury. The Judge saw the note being passed to the lawyer and called him to the bench she asked him if there was a problem with the juror and he said, “we already picked him.” A witness came to us during the trial and said they had seen yet another juror hugging a member of the dead boy’s family. We were told by our lawyer, “don’t bring these things up it will anger the Judge.” An alternate juror was so outraged by what had taken place in the jury deliberation, she called our lawyer crying. She told us how jurors were convinced to change their votes to guilty. How the evidence that was used to convict Anthony was that he wore a school uniform and there was someone seen in the area wearing a uniform. The school was a couple blocks way; there must have been many kids in the area in uniform. The other so-called evidence was that he was not on the phone for 17 minutes that afternoon. The prosecutor said in his closing arguments that the murder took 17 minutes. How would he know how long it took to murder this poor boy? There were other times throughout the day that Anthony had not been on the phone. When he came to my house I made him get off the phone to talk to the family. This was not evidence; this had nothing to do with the murder. The DNA is not Anthony’s. The eye witness said it wasn’t Anthony.

Cheryle:

Sometimes I wish we had left the country. We had that weekend, we could have run away. But we had no idea. We knew he was innocent. We went on vacation. We were so naïve. I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen. Looking back, there were so many things I would have done differently. But you can’t go back. It was the first time we’d been involved in the juvenile justice system. We hired a lawyer we heard was very good. We paid a fortune. My daughter sold her house to pay for him. He let us down immensely.”

[superquote]I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen.[/superquote]

One of my biggest regrets, since we were all going to testify as witnesses, we couldn’t be in the court during Anthony’s proceedings. We waited in the hall every day, waiting to go in, waiting to hear news. Since we weren’t in the room, we couldn’t know exactly how bad our lawyer was.

The juror selection was completely unjust: how was it that when I looked across the room at the jury pool I recognized so many faces? Lake County is HUGE, why couldn’t they pull a more diverse selection of jurors? One of the jurors was from our little community. He was an Elk’s Club member. His wife and the prosecutor’s mother knew each other. This juror gave another juror a ride home to Whiting each day, discussing the case in the car. The trouble with this juror began when he was first selected. He was a neighbor of a niece; it was not a friendly relationship. We knew that it would be wrong for him to be on the jury. My daughter wrote a note during jury selection and asked our lawyer not to allow this juror on the jury. The Judge saw the note being passed to the lawyer and called him to the bench she asked him if there was a problem with the juror and he said, “we already picked him.” A witness came to us during the trial and said they had seen yet another juror hugging a member of the dead boy’s family. We were told by our lawyer, “don’t bring these things up it will anger the Judge.” An alternate juror was so outraged by what had taken place in the jury deliberation, she called our lawyer crying. She told us how jurors were convinced to change their votes to guilty. How the evidence that was used to convict Anthony was that he wore a school uniform and there was someone seen in the area wearing a uniform. The school was a couple blocks way; there must have been many kids in the area in uniform. The other so-called evidence was that he was not on the phone for 17 minutes that afternoon. The prosecutor said in his closing arguments that the murder took 17 minutes. How would he know how long it took to murder this poor boy? There were other times throughout the day that Anthony had not been on the phone. When he came to my house I made him get off the phone to talk to the family. This was not evidence; this had nothing to do with the murder. The DNA is not Anthony’s. The eye witness said it wasn’t Anthony.

[superquote]Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now.[/superquote]

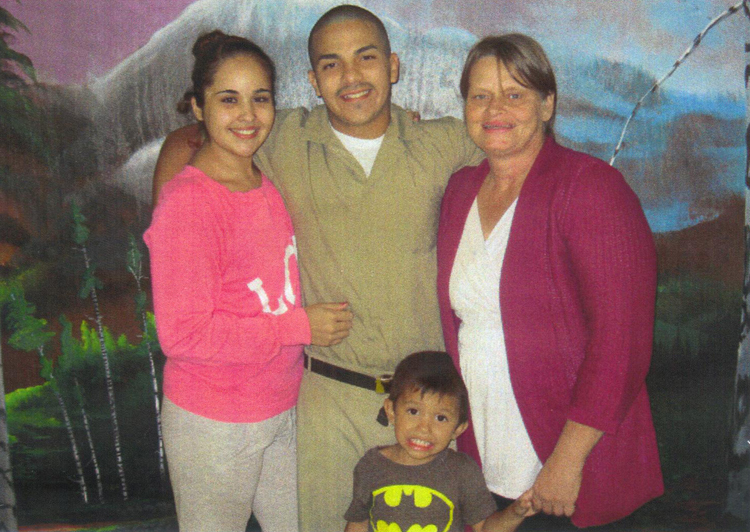

Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now. My granddaughter, Anthony’s little sister, hasn’t been getting enough attention from us. She got lost in all of this. She told one of her friends at school about the whole thing and the parents of the friend forbid their friendship. So she just holds it in, doesn’t tell anyone for fear of reprisal. I have started homeschooling her. She was being bullied. I woke up one morning and realized that whatever energy I had left needed to go towards helping her. She sees a counselor now. At first she didn’t want to visit Anthony, she was scared and so young. But now she visits. We bring in all the kids: the cousins, my 3-year-old grandson, Anthony loves him. Some people question why we bring them in. But they have a right to know each other. He didn’t do anything wrong. Grace [Bauer, of Justice For Families] says you have to do things however you see fit, whatever works for your family. Anthony loves the kids. He talks about driving a car and having kids of his own someday.”

After The Sentencing

“We had a Writ of Cert that was reviewed and denied by the Supreme Court on November 30th. Getting the Writ cost us $8,500.00. My daughter already sold her house, so she sold her car. This should be a right for EVERYONE. It should not be this cost-prohibitive. At least we have these things to sell. It is a sad truth in this system that if you have money, you have a better chance. If you have money and connections you might fare better. There are so many people who can’t afford to take the system on, on any level.”

[superquote]My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime.[/superquote]

My organization, Indiana Families United for Juvenile Justice, had a panel discussion at Purdue University on February 28th, 2013. Grace Bauer of Families For Justice was there, and Karen Grau, Producer of MSNBC’s Young Kids Hard Time, attended. She has met Anthony and she has said how much she likes him. She said he is quiet, and very nice. Those words mean the world to my family. Mark Clemens from Chicago attended. He spoke about being in prison since the age of 16, 28 years for a crime he did not commit. His strength gives us strength. In April I will be attending the JDAI National Inter-site conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Attending will be 180 sites from 39 states and over 700 Juvenile Justice System folks. I am doing what I can to help other families. To be for them what I didn’t have when we started this. Grace has been and is always there for me. I wouldn’t have made it without her. She keeps me hanging on. She tells me, “You can’t let em’ beat you down.” We want to make a manual for other parents and families that are going through this. It’s a complex, often shadowy thing, the juvenile justice system. For many of those involved it’s basically inaccessible. If you don’t have a computer, don’t have internet, you can’t look things up or communicate with others in your position. Having a network is key. Every time something changes in Anthony’s case I email and text everyone to get more advice and information. There is so much I don’t understand.”

[superquote]Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now.[/superquote]

Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now. My granddaughter, Anthony’s little sister, hasn’t been getting enough attention from us. She got lost in all of this. She told one of her friends at school about the whole thing and the parents of the friend forbid their friendship. So she just holds it in, doesn’t tell anyone for fear of reprisal. I have started homeschooling her. She was being bullied. I woke up one morning and realized that whatever energy I had left needed to go towards helping her. She sees a counselor now. At first she didn’t want to visit Anthony, she was scared and so young. But now she visits. We bring in all the kids: the cousins, my 3-year-old grandson, Anthony loves him. Some people question why we bring them in. But they have a right to know each other. He didn’t do anything wrong. Grace [Bauer, of Justice For Families] says you have to do things however you see fit, whatever works for your family. Anthony loves the kids. He talks about driving a car and having kids of his own someday.”

After The Sentencing

“We had a Writ of Cert that was reviewed and denied by the Supreme Court on November 30th. Getting the Writ cost us $8,500.00. My daughter already sold her house, so she sold her car. This should be a right for EVERYONE. It should not be this cost-prohibitive. At least we have these things to sell. It is a sad truth in this system that if you have money, you have a better chance. If you have money and connections you might fare better. There are so many people who can’t afford to take the system on, on any level.”

[superquote]My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime.[/superquote]

My organization, Indiana Families United for Juvenile Justice, had a panel discussion at Purdue University on February 28th, 2013. Grace Bauer of Families For Justice was there, and Karen Grau, Producer of MSNBC’s Young Kids Hard Time, attended. She has met Anthony and she has said how much she likes him. She said he is quiet, and very nice. Those words mean the world to my family. Mark Clemens from Chicago attended. He spoke about being in prison since the age of 16, 28 years for a crime he did not commit. His strength gives us strength. In April I will be attending the JDAI National Inter-site conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Attending will be 180 sites from 39 states and over 700 Juvenile Justice System folks. I am doing what I can to help other families. To be for them what I didn’t have when we started this. Grace has been and is always there for me. I wouldn’t have made it without her. She keeps me hanging on. She tells me, “You can’t let em’ beat you down.” We want to make a manual for other parents and families that are going through this. It’s a complex, often shadowy thing, the juvenile justice system. For many of those involved it’s basically inaccessible. If you don’t have a computer, don’t have internet, you can’t look things up or communicate with others in your position. Having a network is key. Every time something changes in Anthony’s case I email and text everyone to get more advice and information. There is so much I don’t understand.”

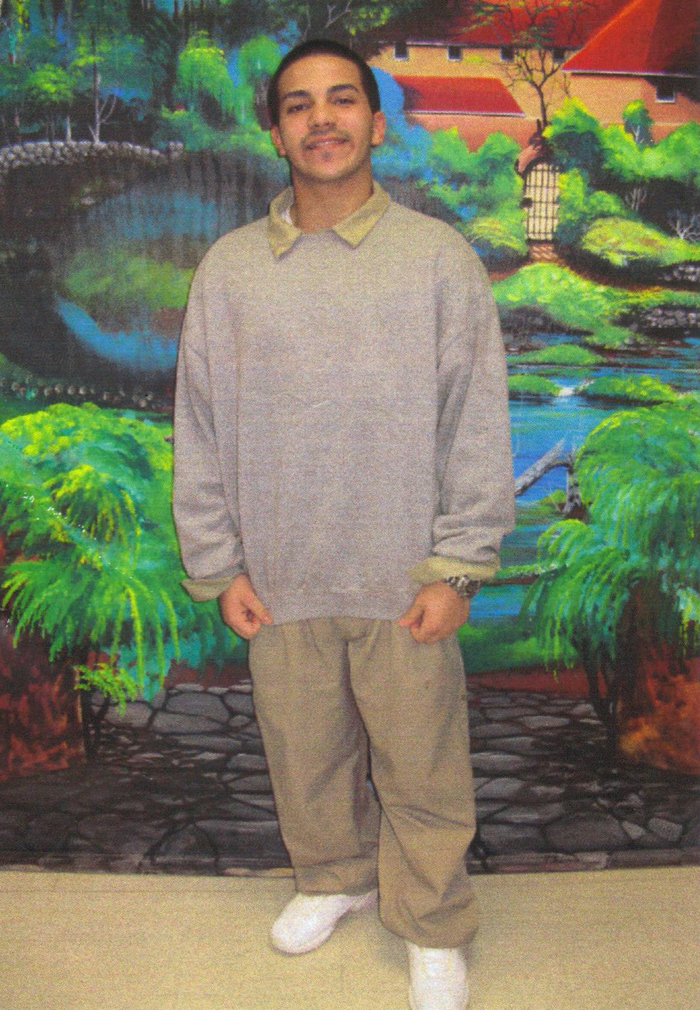

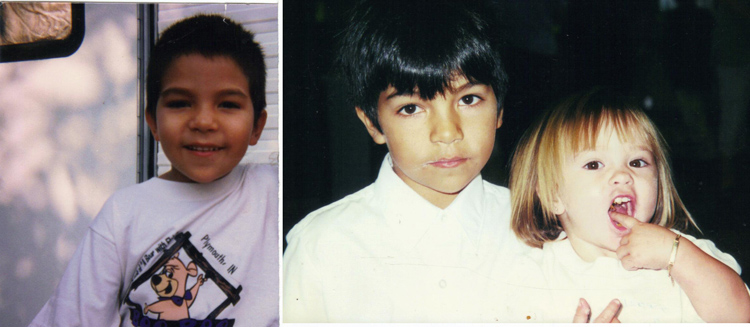

My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime. These are children. They cannot drive, cannot vote, cannot make adult decisions but they can be tried as adults and can receive sometimes even longer sentences than adults for the same type of offences. When we used to visit, Anthony would sit there and say, just tell them I didn’t do it. He tells us he will do whatever it takes; he just wants to come home. Before this, Anthony was beginning 9th grade. In December he celebrated his 5th birthday in prison.

[superquote]He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?[/superquote]

He tells me I feel like I’m 15. I don’t feel like I’m any older. How could he not feel this way? He’s frozen in time and hasn’t been in the world since he was 15. Anthony is in a good program at his prison. He earned his GED and is starting college classes. Because of this program he was able to order rotisserie chicken last week. He told us his tears just came rolling down his face when he bit into the chicken. It breaks my heart that he has lost so much. He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?

My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime. These are children. They cannot drive, cannot vote, cannot make adult decisions but they can be tried as adults and can receive sometimes even longer sentences than adults for the same type of offences. When we used to visit, Anthony would sit there and say, just tell them I didn’t do it. He tells us he will do whatever it takes; he just wants to come home. Before this, Anthony was beginning 9th grade. In December he celebrated his 5th birthday in prison.

[superquote]He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?[/superquote]

He tells me I feel like I’m 15. I don’t feel like I’m any older. How could he not feel this way? He’s frozen in time and hasn’t been in the world since he was 15. Anthony is in a good program at his prison. He earned his GED and is starting college classes. Because of this program he was able to order rotisserie chicken last week. He told us his tears just came rolling down his face when he bit into the chicken. It breaks my heart that he has lost so much. He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?